Thoughts inspired by UX Scotland

1

At the root of user experience design (UX) is the belief that design goes deeper than just artefacts. The key focus of UX are the people using and interacting with what is created. Therefore to practice design is to have influence over the way we interact with society and our environment. This potential to influence highlights a need for design to be seen as intrinsically ethical rather than just a tool.

2

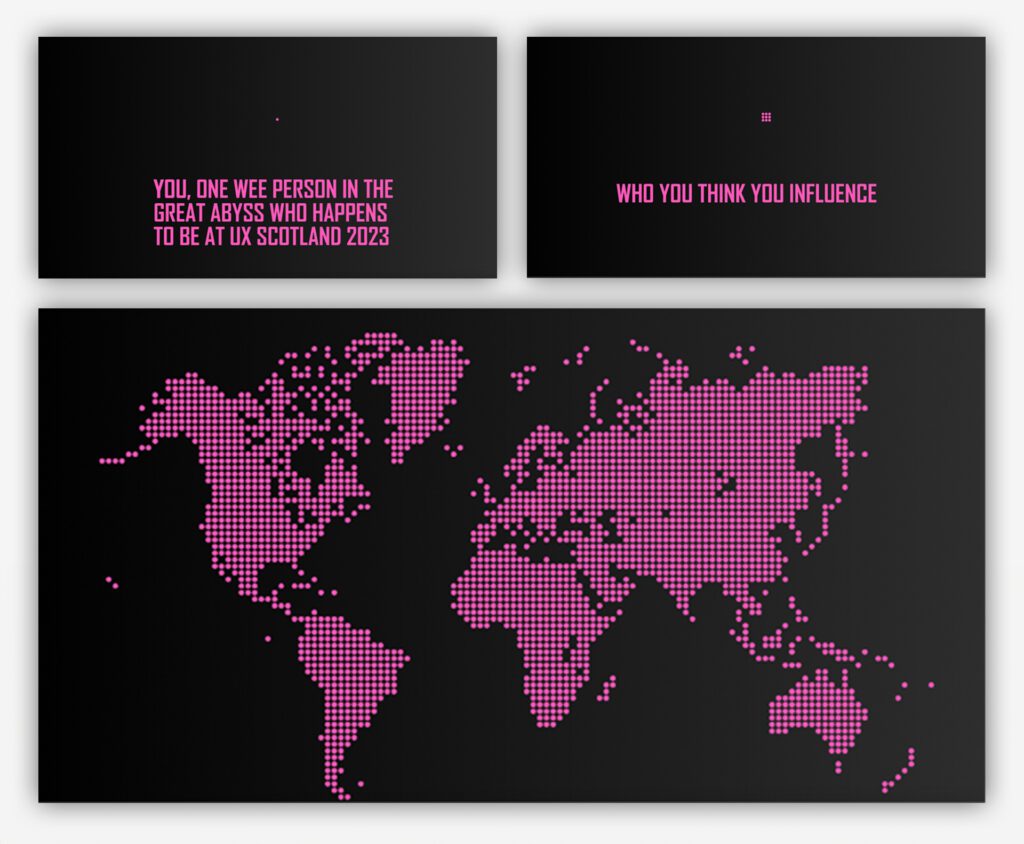

The pressures of societal bias and financial necessity have influence over how true to one’s personal values a designer can remain. However, in her UX Scotland presentation “Design ethically: From imperative to action“. Kat Zhou maintained that; Your privilege x Tech diffusion = Amplified power. The ability to contact and impact others has only grown with the internet and technological advancements. That is why Zhou urged the attendees to not minimise the positive impact they can have as individuals.

3

‘Wicked problems’ is a term used when describing issues which are riddled with uncertainties, nuance and complexities making one clear solution impossible to pinpoint. In his talk at UX Scotland, titled ‘Embracing a complexity mindset,’ Gerry Scullion highlighted some current examples of such complex problems; The COVID-19 pandemic, increasing political divide, climate change, the global food crisis and systemic racism.

4

Scullion stated it was clear that the work to solve these interconnected problems is only going to get harder and they all require a “radical rethink”. He urged the attendees to grow comfortable and lean into working within a “Complexity Mindset” which he defined as being “the ability and acceptance to live, work and thrive within systems that are highly ambiguous”. Fortunately, this is an integral skill held by creative people.

5

To guide designers through tackling these “wicked problems” more conscientiously Kat Zhou has introduced an updated design thinking process:

Empathise, Define, Evaluate, Ideate, Forecast, Prototype, Test, (ship), Monitor. This process is an essential problem solving tool by adding scrutiny and structure to creativity. If this approach was adopted it would hopefully have a ripple effect that would shift the design profession away from supporting outdated systems of power.

6

The randomness and uncertainty that exists within problems is actually a gift. It is the same thing that leaves room for the ability to explore and fully realise what can be done through creativity. This should leave us with hope when addressing these “wicked problems”.

7

Pretending you are working on a simple isolated problem will only cause issues in the long run. Working within this space of high ambiguity creates the potential for outcomes we did not foresee, both good and bad.

8

Zhou put a positive spin on the usually daunting topic of unforeseen consequences. “Forecasted consequences often are design problems.” She suggested that by not underestimating your design’s ability to influence, you could identify many consequences early and solve them pre-launch.

9

At Border Crossing UX we hold the individual person at the core of all communications. Really understanding the target audience is invaluable to us no matter how small the job. Working with authenticity and intention is how we define “good” design. Our vision is “Imagine a better world, and create it” so we take every opportunity to do good by working in line with our values and designing with empathy.

In 2021 as I came to the end of my Graphic Design course I realised that my four final year projects were all exploring the complexities of society and how we are all interconnected. Since my final two years of university were shaded by the pandemic it is not hard to see why this concept occupied my subconscious. During that time it felt like there was a renewed appreciation for the impact we all have on each other at the most basic human levels.

Almost two years later the same concepts were being discussed at the first in-person UX Scotland event post-covid. Many of the talks explored the benefits and difficulties of working in a world that is at the same time growing more connected and more divided.

Tackling big questions

We are very complex beings with emotions, free thought and biases. It is unsurprising that when we come together to work and live that we create complex systems littered with problems and challenges. A large part of being a designer is the ability to problem solve, feel comfortable with uncertainty and guide others to mitigate as many issues as possible. The key-note speeches of Gerry Scullion and Kat Zhou encapsulated this concept excellently. They reminded me of the big questions I was so interested in as a student;

- How can we be more considerate with what we create and put out into the world?

- Once something is created we no longer have autonomy over it, how can we protect as much as possible against its intention being warped?

- Nature has been operating effectively and creatively for so long before us, how can we put the human ego aside to learn from it?

- How mature are the many different design professions in recognising the impact design has on society. How widespread is this discussion?

- How can we convert a conceptual knowledge into actually operating differently in our day to day jobs?

Throughout the conference speakers went a step further than just provoking questions. They provided insights and actionable tools to help us conduct better and more thoughtful design practice.

All professions should be aware of how they can use their skills and expertise to create as much positive net gain as possible. Within some industries this is more overt and very established for example the medical or legal fields. However, within design there are currently minimal governing bodies or legal requirements enforcing a code of conduct or regulations. At Border Crossing UX we believe that design is no different and we all have the ability to self regulate to some degree. It is built into our company values: ‘Driven: We strive to make positive change and are always conscious of the impact of our work.’

Why do designers need to even think about ethics?

Nothing exists in a vacuum – especially design.

What do people actually mean when they say “ethical design”?

Ethics are different schools of thought that encourage critical thinking of who we are and the actions we take. Sometimes the different theories contradict each other which means that something could be considered good when looked through one lens but bad through another. Therefore when people talk about “ethical design” what they actually mean is: design that they define as “good” in relation to their values and view of how the world should be.

Visually good vs morally good

‘Goodness’, whether relating to the aesthetic qualities of design or its social and moral implications, is a subjective topic to discuss. Backed by decades of refinement the design profession is more comfortable critiquing and assessing a design – whether that be graphical, product or service – on its visual appeal. Although we have knowledge to guide us towards “what looks good” in design, for example; colour theory, harmony, contrast and proportions, there is still a large element of personal opinion.

Unfortunately this is also true with questions of morality, values and ethics. Perhaps one could argue that beautiful things bring joy to society and therefore we could say they are good without further interrogation. However, it is nearly impossible to separate form from function. For example, when graphic design is visually appealing it does a better job of infiltrating its target market. Therefore even when attempting to decide whether design is visually proficient, the viewer quickly looks at it through the lens of society, circumstance and personal bias. This means that individual designers should strive to create aesthetically appealing work but with the caveat that in many ways the visual is interwoven with impacts on the public.

Ethical philosophies as guidance

At the root of user experience design is the belief that design goes deeper than just artefacts. The key focus are the people using and interacting with what is created. This means that to practice design is to have influence over the way we interact with society and our environment. By the nature of the design process designers are continually making decisions and creating outcomes that have impact in situations. This creates a great responsibility. In other words, design’s impact on what it means to be human, through the creation of artefacts and materials, highlights a need for design to be seen as intrinsically ethical rather than just a tool.

Without doing a disservice to the massive and nuanced topic of ethics and design ethics it is important to note that each branch of ethical philosophy can provide designers with lessons or guidance on how to navigate the design profession more constructively. Arguably these propositions eventually reach their limit and cannot guide us any further through the difficult, emotional and personal complexities of life. Personal circumstance and responsibilities; whether financial, religious or relational, have an impact on how we behave. This is no different in the professional field for designers.

Designing in a complex, interconnected world

Should the ethical responsibility be on the individual?

The pressures of societal bias and financial necessity have an influence over how true to one’s personal values a designer can remain. There is often a distance between what they care about and the day-to-day expectations from the design sphere that will employ them. Therefore some may say that it is not feasible to place the burden of being an ethical designer purely on the individual.

However, in her presentation Kat Zhou maintained that; Your privilege x Tech diffusion = Amplified power. Meaning that we all, especially those with privilege, have a burden of responsibility. Whether designing a product, service or campaign to persuade or influence, there is a duty to be aware of the wide range of possible consequences. The ability to contact and impact others has only grown with the internet and technological advancements. We are all aware of the negativity and harm that can be done through the misuse of this power. That is why Zhou urged the attendees to not minimise the positive impact they can have as individuals.

Influence and breaking echo chambers

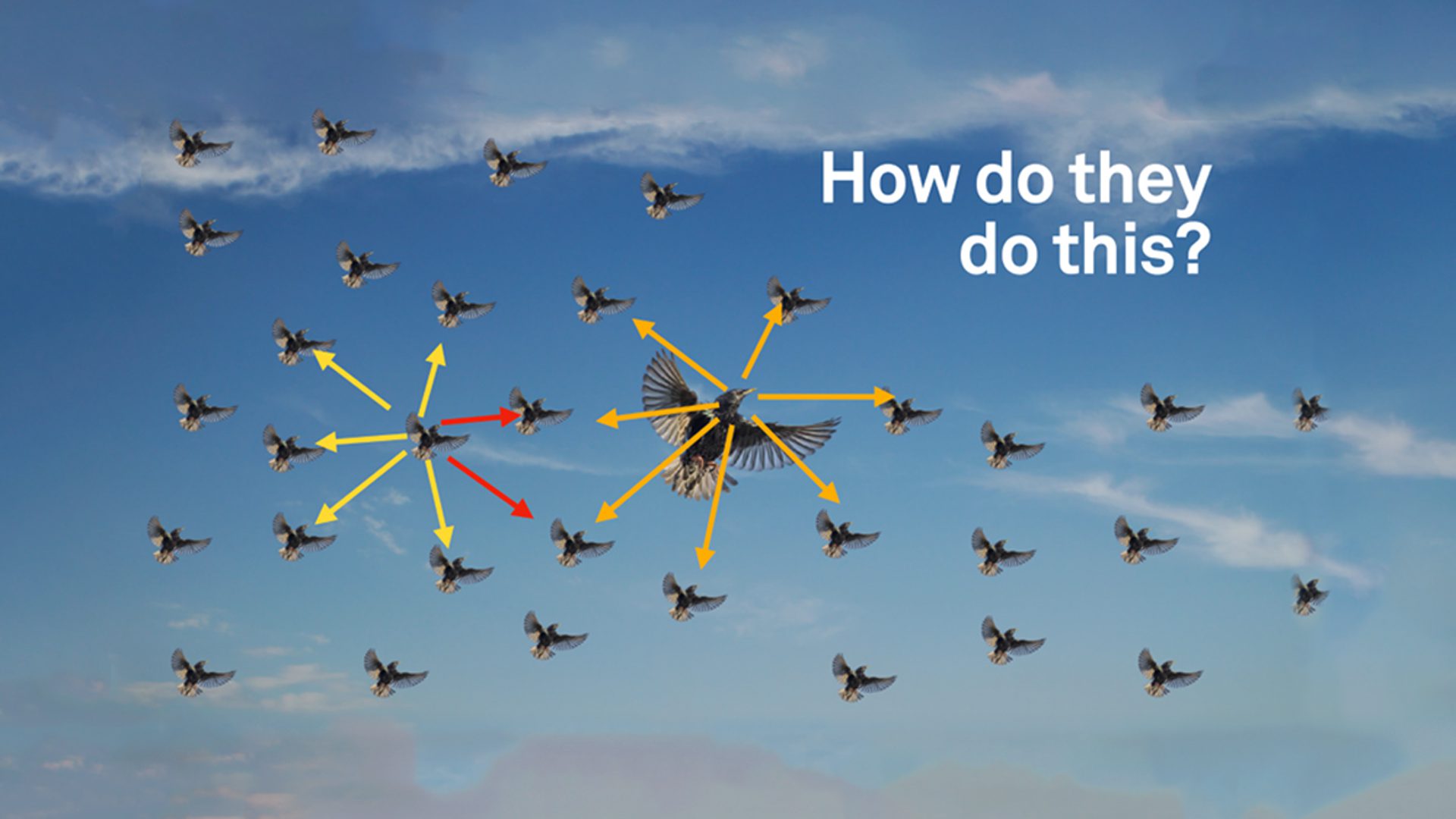

Gerry Scullion also impressed the importance of the chain reaction by using a murmuration of starlings as a metaphor. There is a lot to be learned from how these birds operate with extreme agility. The birds fly in unison by being in tune with those around them. As they search for food, they adapt their trajectory and speed depending on feedback from the other birds so that they continuously work as a team. Scullion observed “This is a complex system. There are feedback loops, there is interconnectedness, there is unpredictability and low-level randomness is present” – just like our societies. Starlings can serve as a reminder that we all have people in our lives that we influence, they influence others and in turn, we are influenced by them.

This phenomenon presents itself negatively by creating echo chambers of knowledge and inspiration which, as Kat Zhou illustrated, contributes to;

- Similar designs, design patterns and therefore the same design mistakes, time and time again,

- A focus on the same types of users over and over, often overlooking marginalised communities,

- A focus on profit and excelling under capitalism,

- All of which ultimately uphold systems of oppression.

But it is the same human nature that makes it possible for designers to make positive changes.

“Humans are complex. Humans interacting with other human beings is exponentially more complex.”

Gerry Scullion

An amended design process

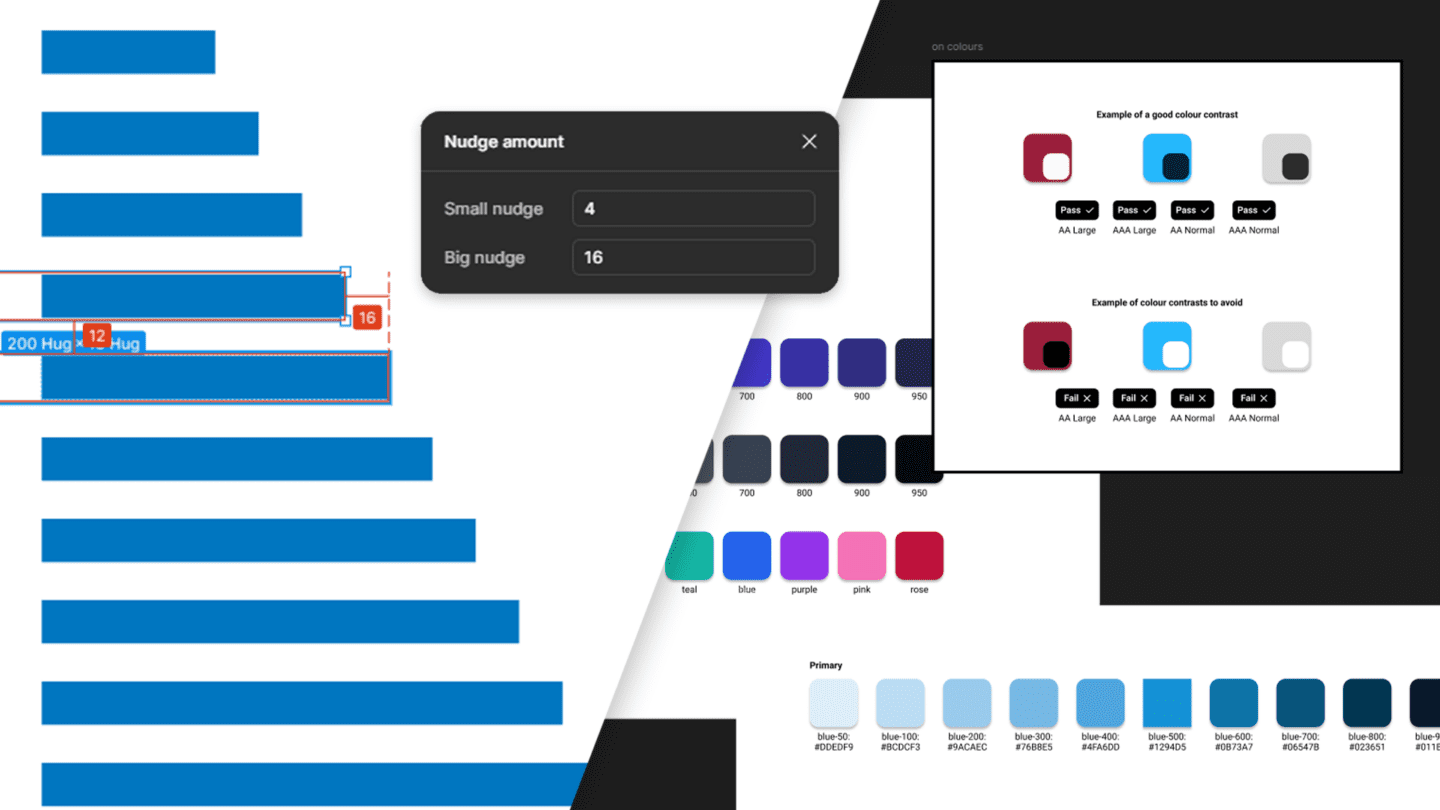

To guide designers through this, Zhou proposed an amended design process.

As it stands the generally used design thinking process is:

Empathise, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test

But Zhou has introduced a few more steps:

Empathise

Define

Evaluate

Ideate

Forecast

Prototype

Test

(Ship)

Monitor

By adding Evaluate:

Designers are asked to really reflect and be honest about whether the project needs to be undertaken. Ethically, does the problem statement from the “define” stage even need to be addressed? Perhaps the “problem” is just a difference in culture, or perhaps it is just creating something new to gain money at the expense of the environment.

By adding Forecast:

Designers are asked to look forward and interrogate the potential outcomes of the project, both short and long term. Primary and secondary outcomes are often monitored through KPIs and OKRs, but what about Tertiary outcomes that might be unforeseen unless questioned? What societal or ethically questionable implications could the work have?

By adding Monitor:

The designer is responsible for the project for a longer stretch of time. This is the stage to be honest about any ethical violations that have occurred and adapt and improve the design accordingly.

This process is an essential problem solving tool, it adds scrutiny and structure to creativity. If this approach was adopted it would hopefully – like in a Starling murmuration – have a ripple effect that would shift the design profession away from supporting outdated systems of power.

Wicked Problems and working with a Complexity Mindset

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber (1984) coined the term ‘wicked problems’ when describing issues which are riddled with uncertainties, nuance and complexities making one clear solution impossible to pinpoint.

Gerry Scullion highlighted some current examples of such complex problems; The COVID-19 pandemic, the increasing political divide, climate change, the global food crisis and systemic racism. Due to the points highlighted previously by Kat Zhou, we should also include the design industry being outdated – definitely in diversity and sometimes in techniques – as a wicked problem.

Uncertainty leaves room for creativity

Scullion stated it was clear that the work to solve these interconnected problems is only going to get harder and they all require a “radical rethink”. He urged the attendees to grow comfortable and lean into working within a “Complexity Mindset” which he defined as being “the ability and acceptance to live, work and thrive within systems that are highly ambiguous”.

Fortunately, this is an integral skill held by most creative people. The activity of design innately holds not only the evolution of things that are tangible but also an expansion beyond what can be imagined. For example, in the early design of the car, Henry Ford is rumoured to have said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.” There may not be truth behind him saying this but the point is still illustrated. When users are asked for input, transportation is limited by only improving what already exists in their world. Design is, without question, a practice of stretching possibilities by creating, prototyping and testing to materialise new outcomes – perhaps that have never been realised before.

The randomness and uncertainty that exists within problems is actually a gift. It is the same thing that leaves room for the ability to explore and fully realise what can be done through creativity. This should leave us with hope when addressing these “wicked problems”.

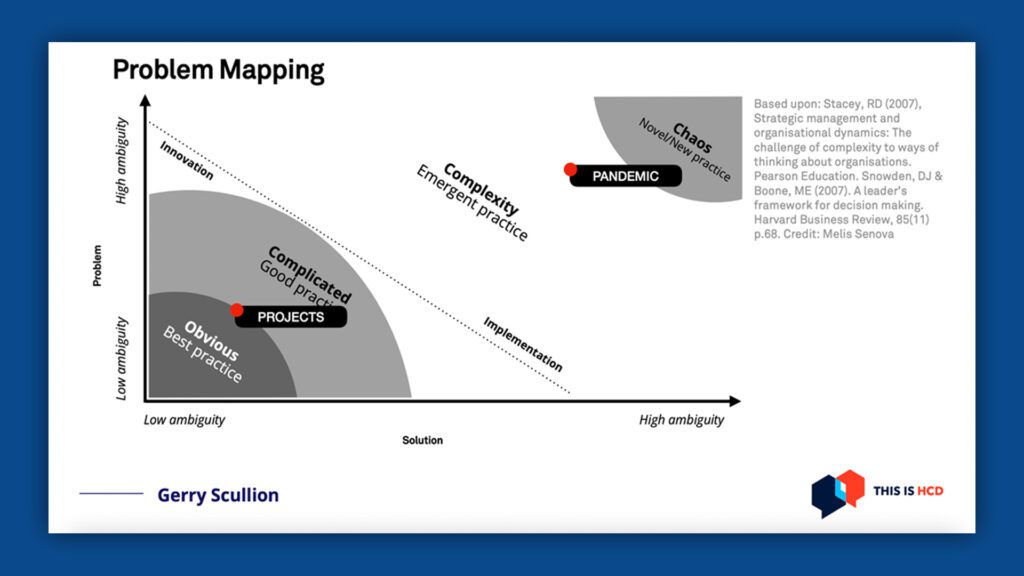

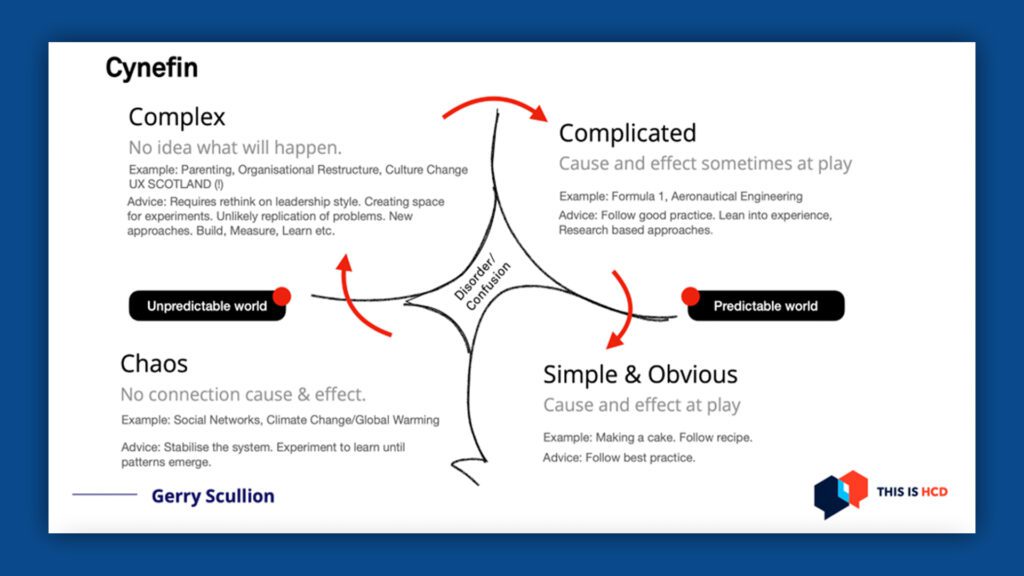

Problem Mapping

As well as Zhou’s actionable new design process, Scullion provided new perspectives on some well used UX tools. He introduced Problem Mapping and using the Cynefin Framework (images below). One of the first steps to successfully working on “wicked problems” is being able to see and articulate to others when you are operating in this space. Acknowledging that things are interconnected and complex allows you to authentically follow Zhou’s updated design process.

The goal is to use this design process to increase your knowledge and these new mapping tools to nudge your problem around the matrix clockwise as far as you can from Chaos to Complex to Complicated to Simple & Obvious. This is a valuable tool in being able to show stakeholders where the project or problem is currently and what your plan is to resolve it and deliver a positive outcome.

Pretending you are working on a simple isolated problem will only cause issues in the long run. Working within this space of high ambiguity creates the potential for outcomes we did not foresee, both good and bad. Zhou put a positive spin on the usually daunting topic of unforeseen consequences. “Forecasted consequences often are design problems.” She suggested that by not underestimating your design’s ability to influence, you could identify many consequences early and solve them pre-launch.

Conclusion: Choice

There can be fear associated with the concept of interconnectivity. If you dwell too much on the many ways we all consciously and subconsciously impact each other and the environment; it can lead to a feeling of paralysis. It is understandable that there can be the mindset of, “If I can’t do anything right or without accidentally impacting someone negatively; I will just opt out of this discussion altogether”. Societally we can see this burnout appear in most contentious discourse; from climate change to political and racial divides.

It makes sense that this tension can carry over into our professional lives. It is hard to navigate which projects to take on or which to turn down. It is valid to overthink how something you create might be perceived. It is difficult to know how long to spend pouring energy into something that might not change. But all of this just gets harder when doing it in the echochamber of your own head. That is where designing in an interconnected world can be a blessing.

Interconnectivity as an advantage

There are many designers and collaborations working to make the design industry more aware of its effect. There are loads of great people doing great work to advocate for marginalised groups, improve accessibility standards and staying humble enough to admit when things need to change. Ultimately you do need to actively opt-in to working in this way. But if you do it is not something you can do alone.

For example if you are concerned about the unintended impact your design might have, the key is discussion and being humble. You can learn from previous research and speak to people who have implemented a similar thing. Definitely learn from experts or the people who will be impacted. Iterate and test and iterate again. All of this connection helps you acquire knowledge, challenge your hypotheses and ultimately minimise your mistakes.

We all need to make the effort to continuously remind ourselves to question, critique, check our internal biases and challenge clients to do better too.

Working with authenticity and intention

At Border Crossing UX we hold the individual person at the core of all communications. That is our grounding force that helps guide us through difficult situations. Finding your own personal or organisational equivalent could be very helpful. Really understanding the target audience is invaluable to us no matter how small the job. Working with authenticity and intention is how we define “good” design. Our vision is “Imagine a better world, and create it” so we take every opportunity to do good by working inline with our values and designing with empathy.

The way the design thinking process works through problems with empathetic research, prototyping, testing and iterations, makes it very effective in tackling complexity and creating new possibilities. This was the sentiment held by many speakers at the UX Scotland conference and is what we try to remember through every project at Border Crossing UX.

Our creativity is perfectly set up to spark positive change if we choose, and are empowered, to use it in that way.