As a young designer who is continuing to learn how service design is applied within large and complex organisations, attending Service Design in Government was extremely valuable. Every single talk I was able to go to either taught me new skills, introduced new coping strategies, or validated concepts I was already familiar with.

Despite the vast range of job titles and levels of expertise of those attending the conference, it was clear to me that the one thing underpinning it all was a strong sense of caring. Every speaker seemed to be driven by a deep emotional push to make services better for the users. This sense was reflected back by the audience in the form of lots of nodding heads, enthusiastic clapping and genuine questions to spark discussion.

Navigating the difficulties within Service Design

Probably due to the level of emotional investment of everyone who chooses to work in the Service Design discipline – or in one of the many interconnected roles – a strong theme of frustration was also palpable. It seemed that there was a real risk of burnout from many of the attendees due to the struggles of advocating for change in organisations that are steeped in governance and move at a slow pace. As Kate Tarling said in her keynote speech, sometimes it can feel like you have been tasked to drive an oil tanker but have been placed nowhere near the tiller. The nervous chuckle this received indicated a clear consensus.

Fortunately, many of the talks offered not only a strong sense of support, understanding, and community but, even more importantly, practical strategies and tools to help navigate these challenges. As Rochelle Gold reminded us in her Keynote “Journey to Eutopia”, progress should be the target not perfection since we will never have the resources, time and money to reach and provide the “perfect” service.

Embracing the difficulties.

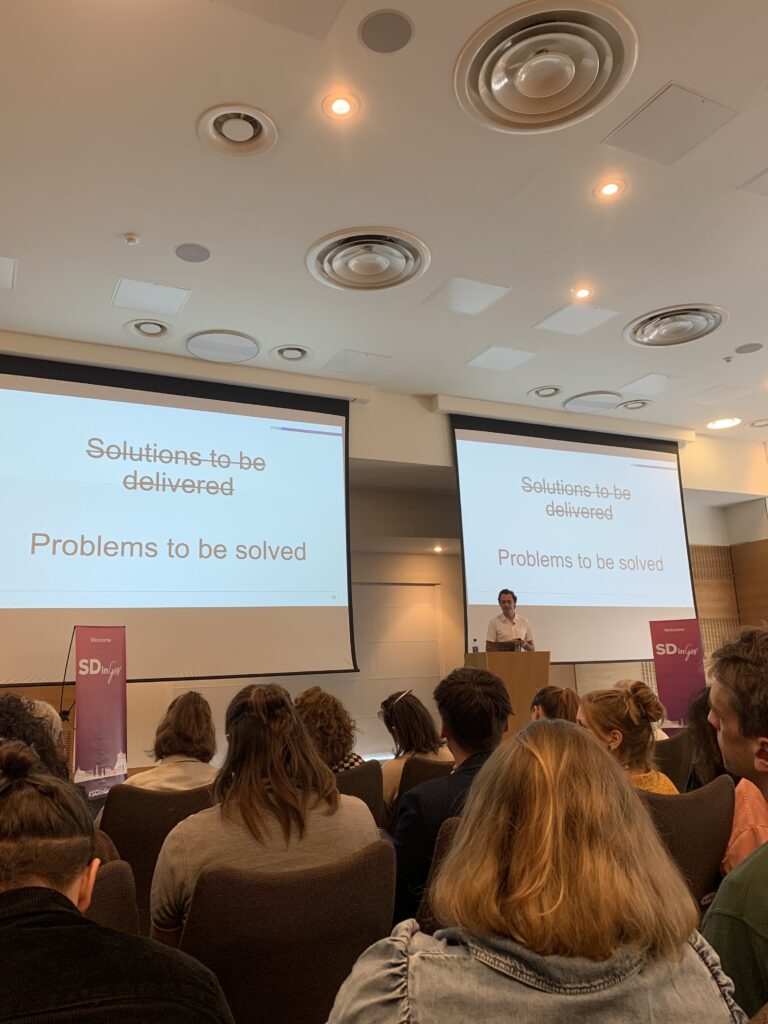

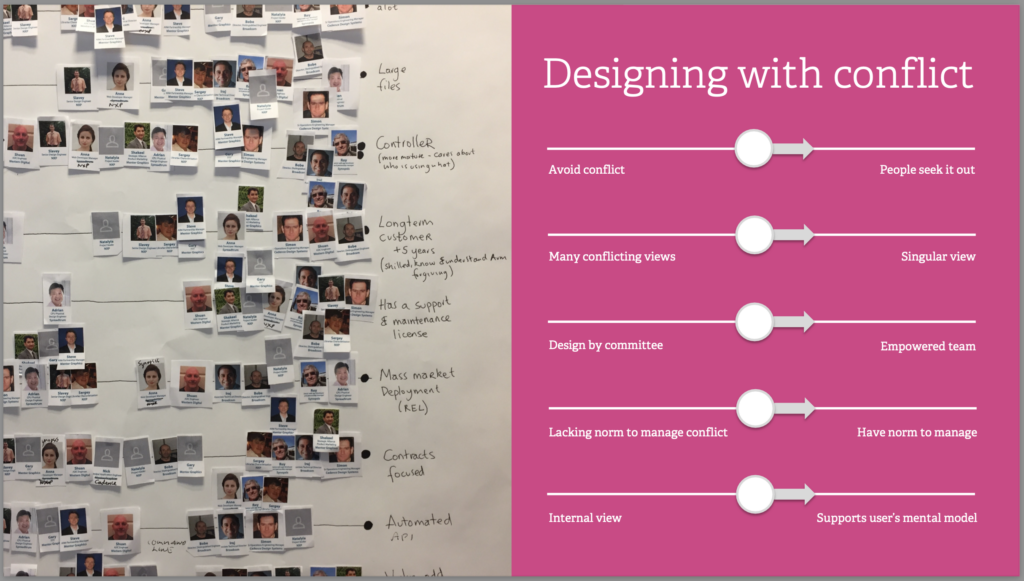

So many speakers articulated and shared practical tools to help us with making this progress. Actionable take-aways like this are so valuable for those of any experience level; especially when they aim to spark a different way of thinking or a new perspective. In his talk “Resetting to design with impact”, Alan Colville reframed some of the key issues that crop up time and time again as being things we can use to our advantage. Conflict, Complexity, and Uncertainty – these are at the core of every project tackled by designers and can clearly be the source of a lot of tension. But knowing how to harness their ability to make us think differently, push us to better outcomes, and spark creativity, is key to actually reaching successful outcomes.

Care and communication

The skill underneath designing through conflict, complexity, and uncertainty is the ability to care about what other people care about. Whether that be money, targets, or a different service from the one you are working on. We need to be able to guide them through a period of anxiety, understand what they have on the line, and “speak the language” of whomever you are communicating with. This sentiment was strongly advocated for by many of the speakers.

Clever communication

When starting your career, a way to learn how to speak to different stakeholders and understand differing points of view is by asking to be invited to meetings. Kate Ivey-Williams shared this as one of her “lessons from the field”. By being in the right spaces you will absorb the right information and eventually may be able to answer a question or offer insights and advice.

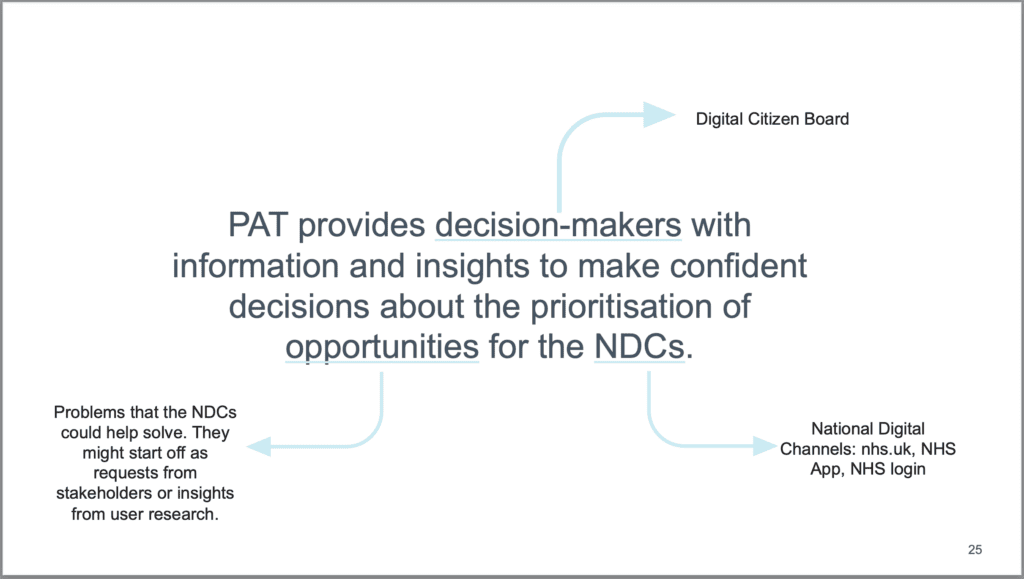

Being able to position your opinions and ideas in the correct way is really key in seeing them being moved forward by senior stakeholders. This was key advice from James Higgott when he shared tips on “How to influence the strategic direction of large, complex services”. After all, whatever the decision maker deems as most valuable, is what gets done. His team designed a process to aid decision makers in prioritising opportunities for development.

An interesting take away from his talk was the importance of seeing every process as a service; if the process is easy and enjoyable to go through people are more likely to opt in and choose to undergo it, therefore making it more successful and more likely to fulfil the business need. Services need time to mature and strengthen as they move from something novel for the user to “the way things are done”. An important practice to remember is to build in metrics and measurements of success from the very start, even if the future of the new process or service is uncertain. This way, if it does achieve anecdotal ‘success,’ you can evidence this with data to back it up.

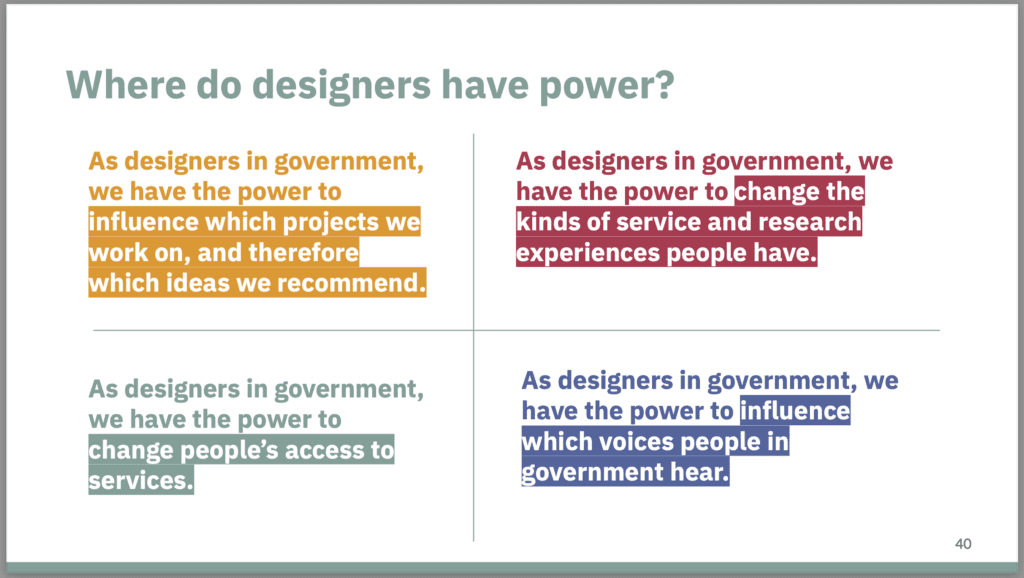

Privilege, power and imagination

As well as professional lessons learned – many more than just the ones mentioned above – there were also some really great personal and societal points to take away and think about. This is unsurprising as who we are as people translates fully into our work. It was lovely to see all of the speakers being so open with who they are, what they struggle with, and what inspires them.

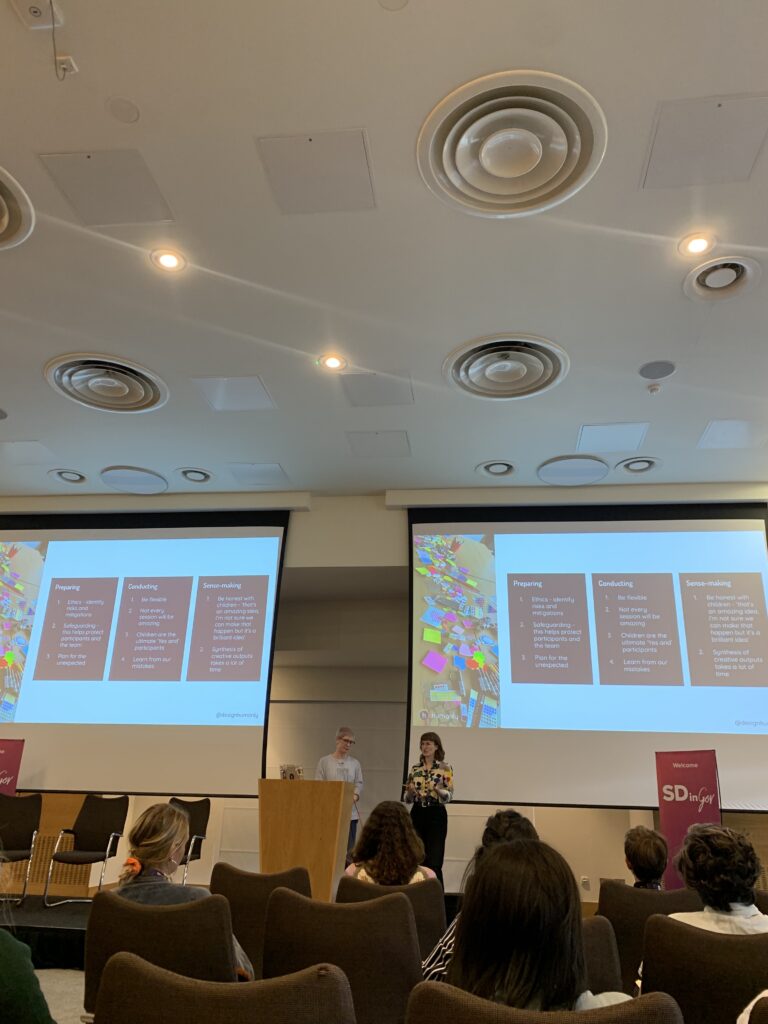

Jane McFadyen and Anna Khoury did an amazing job being informative and vulnerable in their talk, “Designing for people with dyscalculia or low numeracy”. It was part raising awareness of an often overlooked accessibility need, part practical design guidance. The research backed advice on how to make our services, forms, and experiences easier for people who struggle with numbers was extremely valuable. It is one thing to know something is difficult and a completely different thing to know how to professionally improve it. The advice they gave was backed by strong research and reviewed by experts. The government leading the way in improving accessibility standards is vital due to the reach and power their services have. The robustness of their advice allows designers working for agencies and in the private sector to also improve their work and confidently advocate for changes to be made.

Understanding power

Power is such an important and nuanced human dynamic that is at play constantly. There is a lot to unpack, especially through the lens of designing for the government. But, an interesting perspective to not overlook is that silence can be a form of resistance or a symptom of oppression. This was articulated well by Delina Evans and Talise Tsai in “Addressing power, bias & potential harm in design for cultural diversity.” In their workshop they encouraged us to challenge the very white, western expectation of cultural norms. They cited a really interesting piece of academic writing that explored the experience of a person being kept waiting by the state / government, often during very important processes. “Waiting is an internalised form of discipline where people are socialised to become compliant, feel subordinate, and dependent.”

An effect of misused power

By making our government services hard to interact with we are contributing to the oppression of many vulnerable groups. If someone grows used to this and doesn’t see that there could be change, they might remain silent when asked for feedback. As service designers or researchers, we should remember that this silence might not mean “everything is fine” it might be flagging the deeper issue of someone being unable or unwilling to imagine better.

This was reinforced by Julian Thompson in his very well received keynote, “Transcending Black Realities: The Possibilities of Joy & Imagination”. If someone cannot picture or even express anything better for themselves due to years of trauma or living moment to moment, how can they be expected to put in place actions to improve their situation. As people of privilege, and people working towards the change of services and society, it is our job to facilitate a reconnection to imagination for those who can’t easily access it.

Reality balanced with hope

Overall it was a very interesting three days that shone an honest light on the struggles of the industry. It was acknowledged that it is sometimes an uphill battle to get things changed within government. Whether that be navigating governance and policy to make small scale changes or improving the understanding of Service Design as a discipline. There was a strong sense of positive community but it was also reassuring to see and hear a healthy amount of humility and readiness to improve. There are certainly a lot of good people doing a lot of good work towards increasing the diversity and inclusion of the profession and, most essentially, within our government services. I left with a lot of hope that collectively we will continue improving by; working across disciplines, cleverly communicating and encouraging differing perspectives.

There were so many amazing talks and speakers to learn from so we highly recommend reviewing the slides attached to the programme.